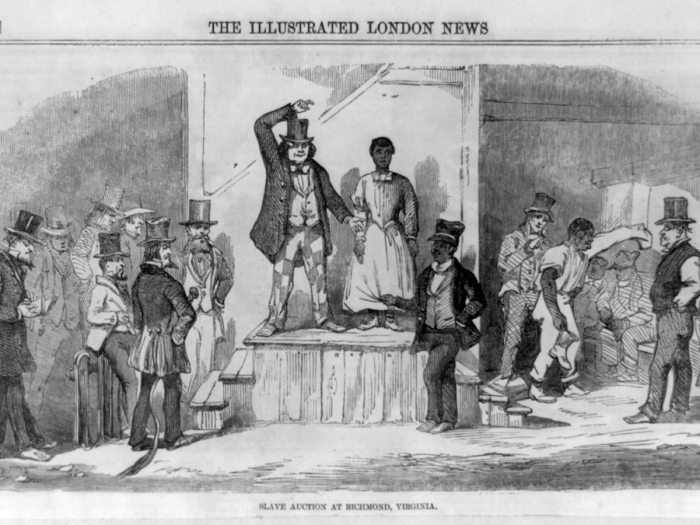

The Significance of the Trade

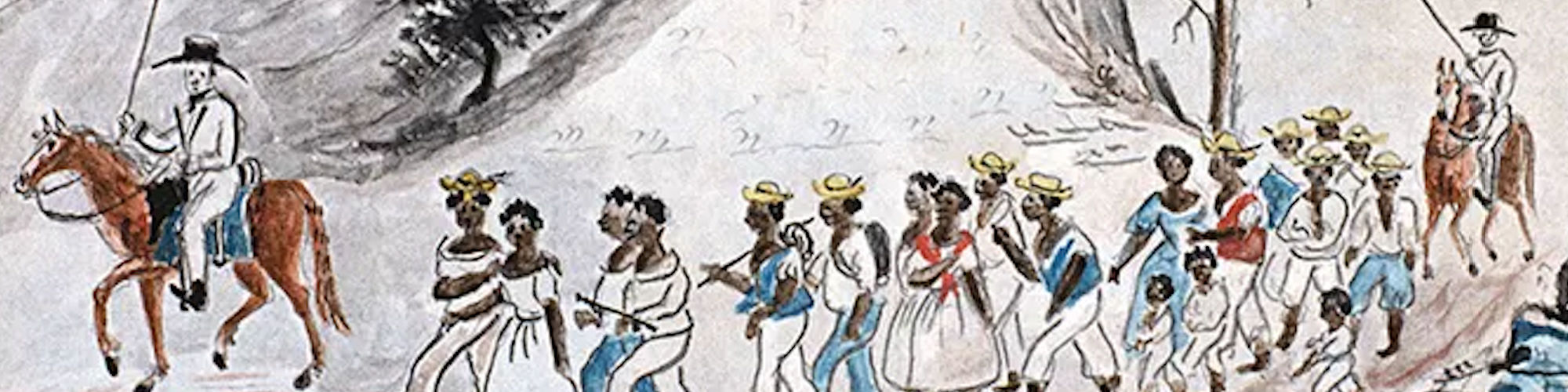

In 1972, historian Richard Ralston coined the term ‘Second Middle Passage’ as a way of conveying the devastations to the Black community caused by the domestic slave trade in the United States. In this second wave of the larger African diaspora more than a million men, women, and children were sold ‘down the river’ from the upper south to the newer states of the Cotton Kingdom.

In his original draft of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson famously charged his king with human trafficking: “He has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life & liberty in the persons of a distant people [meaning Africans] who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere [meaning America] to incur miserable death in their transportation thither.” This passage was so inflammatory it was removed.

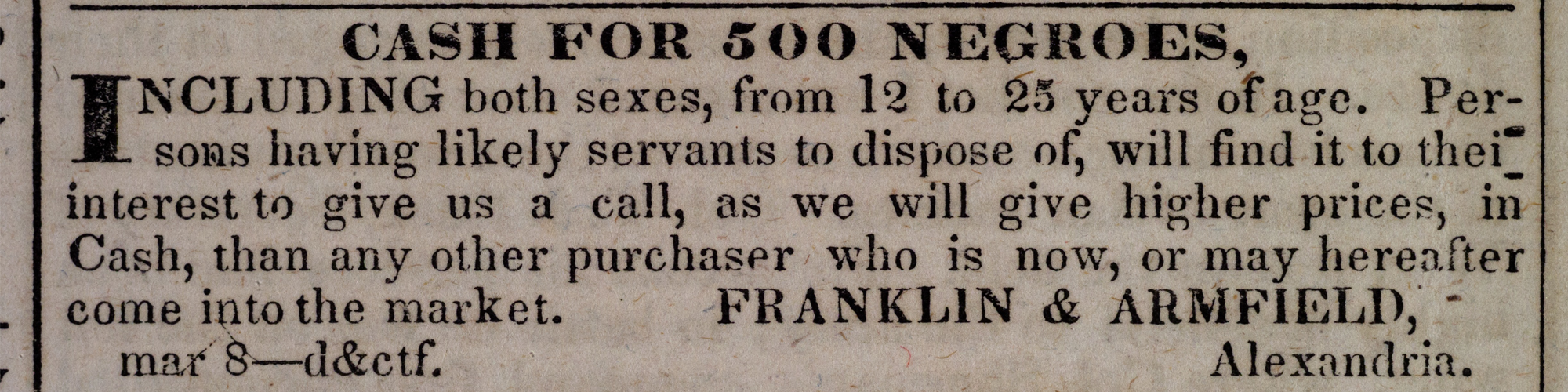

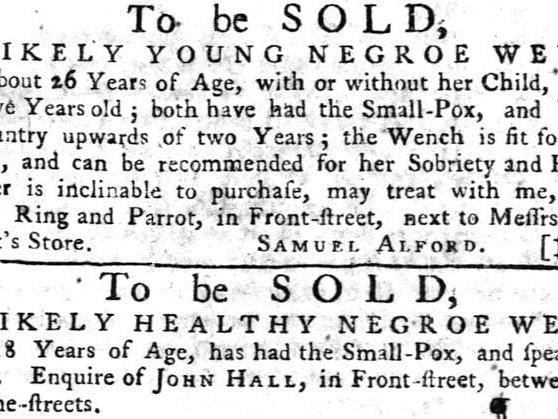

What Jefferson never acknowledged, but participated in, was the subsequently massive trade in human beings.

Historian Tiya Miles has told the harrowing history of Ashley’s sack, a simple cotton bag given from an enslaved mother, Rose, to her nine-year-old daughter on the occasion of her daughter’s unexpected sale. Heartbroken at having to say a sudden goodbye, Rose repurposed the bag as a psychic med kit, filling it with a dress, some pecans, a braid of her hair, and “my love always.” She never saw her daughter again.

To understand the devastation of the Second Middle Passage, multiply this story by a million.

And then understand that such sales were but a fraction of the transfers that occurred not between states but within states as a result of sheriff’s sales, probate sales, and private agreement.