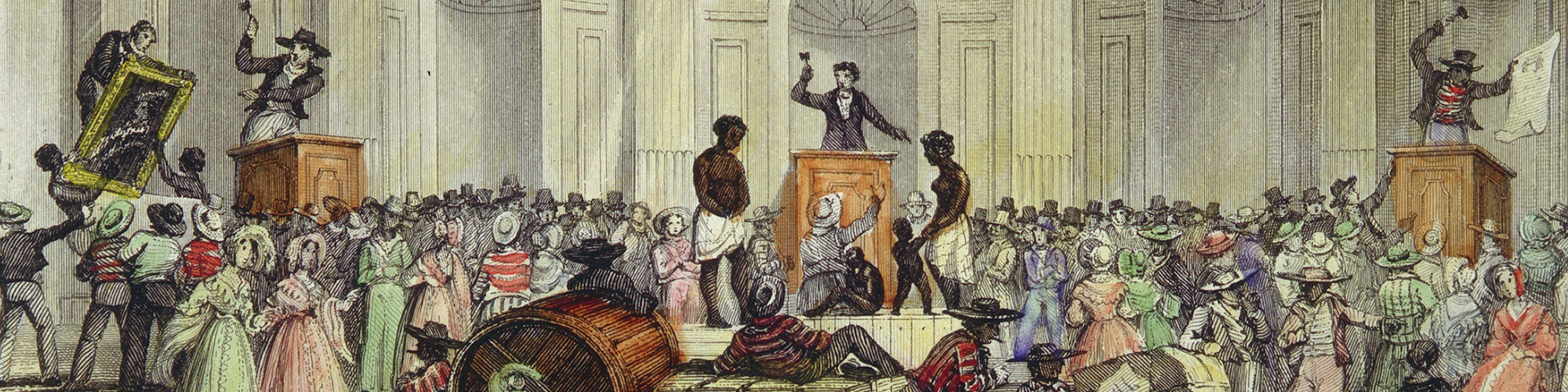

Slave sales were more omnipresent, central, and diverse in form than is generally understood. Beyond the formal slavetraders, Justices of the Peace issued executions for sheriffs to seize and sell property (in order to pay off debts), and this property often included enslaved people, sometimes small numbers, sometimes large ‘gangs.' The same holds true of advertisements for trustee’s sales and probate sales. Archivists routinely tell researchers that state laws required the official recording of all sales of enslaved people, but pilot studies comparing official state ledgers of sales with sales reflected in newspaper advertisements clearly indicate that those recorded in official ledgers represent, at most, a few percent of all sales. Official recording could give extra security to buyers, but hand-written bills of sale sufficed and were everywhere legally binding. The disappearance of so many hand-written records powerfully underlines the importance of newspaper advertisements.

The nature and scale of To Be Sold promises to open up research on many aspects of slavery, racism, and American society. Work by Michael Tadman (Speculators and Slaves [1989, expanded 1996], and with some updating in his essay in Johnson, The Chattel Principle [2004]) seems, in broad terms at least, to have established the overall scale of the inter-state slave trade. So far as local sales are concerned, however, we have only very tentative evidence, this mostly coming from a local South Carolina-based study by Tadman and important work by Thomas D. Russell. Most of the court and private sales noted above would have been local and intra-state, although traders would have intervened and made their purchases when the terms of sale were convenient—cash rather than extended credit, and when those sold were ‘likely’ (healthy and promising good returns) teenagers, young adults, or women with a young child. Newspaper advertisements will not capture those local sales which were simply private agreements between individuals. Nevertheless, our database captures huge numbers of local sales and, by developing systematic samples of advertisements by date and location from across the South, it provides the first rigorous region-wide evidence on the scale of local sales. Furthermore, our data on the relative numbers of various classes of sale (probate, sheriff etc.) might allow us to estimate the combined numbers of advertised and non-advertised private sales. To achieve this we are working with appeals court cases concerning sales and looking at the ratio of disputed private sales compared with other classes of sale.

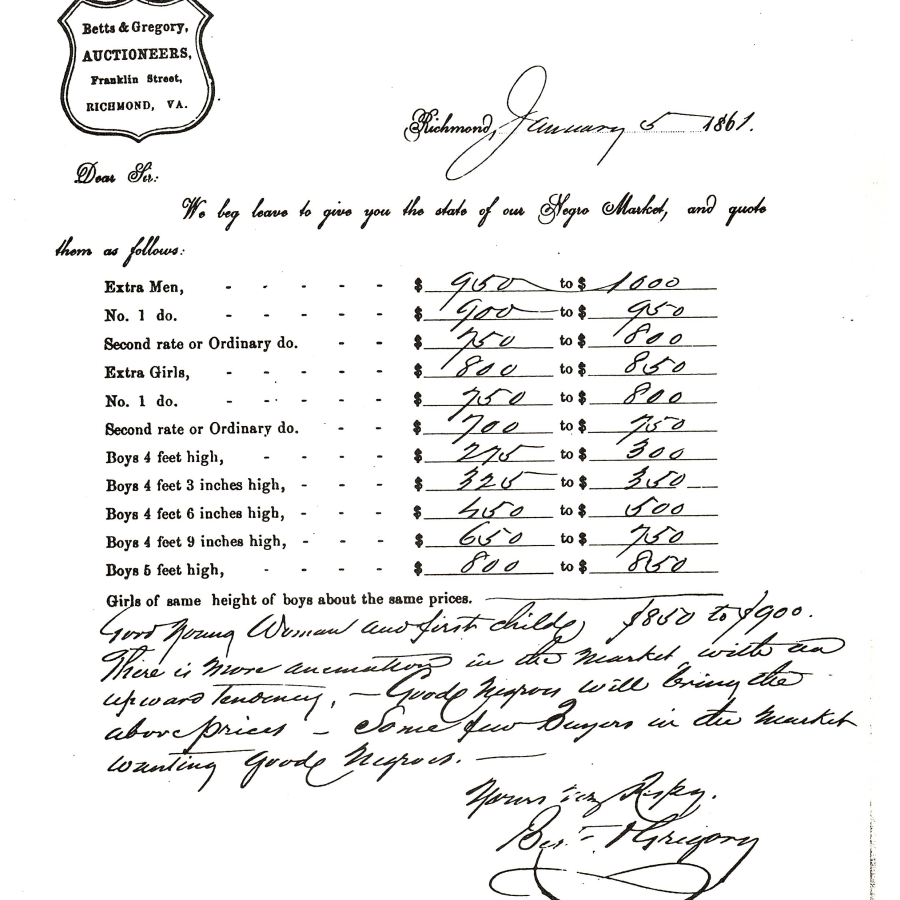

Studies of the inter-state slave trade have boomed since Tadman’s 1989 study but have concentrated on a few mostly urban locations, especially Richmond, Charleston, and New Orleans. To Be Sold provides a basis for studying the trade in close detail in every southern state, as well as in the northern and middle states during the early-national period when they sold many people south. Robust extended estimates of the scale of local sales might well suggest that those sales were three or four times as numerous as inter-state sales, a calculation that would raise the number of enslaved African-Americans sold from an inter-state figure of over 1.2 million (Tadman) to the enormous total of some 5 to 6 million people sold either locally or inter-regionally between 1790 and 1865. Firm evidence on buying and selling on this scale will present scholars with major new contexts to digest when asking questions about the Black experience, the Black family, white attitudes to slavery and Blackness, white rationalisation and exploitation, and the role of Black bodies in American capitalism.